A 15-Year Strategic Bet Enters Its Harvest Phase

On February 16, 2026, Japanese trading house Sojitz Corporation formally announced an expansion of its rare earth element imports from Australia’s Lynas Rare Earths, adding new product categories and signaling the most significant milestone yet in Japan’s decade-and-a-half campaign to diversify its critical minerals supply chain away from Chinese dominance. The partnership between Sojitz and Lynas dates back to 2011, initiated in the immediate aftermath of China’s 2010 rare earth export restrictions that sent shockwaves through global manufacturing sectors dependent on these irreplaceable materials. That crisis fundamentally rewired Japanese industrial policy, embedding a core principle into Tokyo’s resource security doctrine: never again allow a single nation to hold veto power over the supply of strategic minerals.

The fruits of this long-term investment began materializing in October 2025, when Sojitz commenced imports of heavy rare earth elements — dysprosium and terbium — from Lynas. These elements serve as critical additives in high-performance neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB) permanent magnets, directly determining the thermal stability and efficiency of electric vehicle drive motors and wind turbine generators. Now, Sojitz has announced that it will add samarium imports beginning April 2026, with plans to expand to as many as six medium and heavy rare earth elements by mid-2027, including gadolinium (used in MRI contrast agents and nuclear reactor control rods) and yttrium (essential for superconducting materials and specialty ceramics). Japan’s rare earth diversification is transitioning from targeted point solutions to comprehensive coverage across the entire critical elements spectrum.

China’s Tightening Export Controls Create Unprecedented Urgency

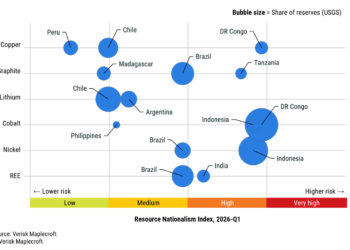

The strategic context for Sojitz’s accelerated timeline is defined by an increasingly adversarial minerals trade environment. China currently controls approximately 85% to 90% of global rare earth refining and separation capacity, a concentration ratio that far exceeds its share of upstream mining. This distinction matters enormously: while rare earth ores can be found across multiple continents, the chemical separation processes required to transform mixed concentrates into individual high-purity oxides remain overwhelmingly concentrated within Chinese facilities. Lynas occupies a uniquely strategic position as the only company outside China operating commercial-scale separated rare earth oxide production, with its LAMP processing facility in Kuantan, Malaysia, and Mt Weld mine in Western Australia forming an integrated mine-to-refinery value chain.

In January 2026, Beijing further tightened its critical minerals export control regime, with reports from the Wall Street Journal and other outlets indicating that Chinese authorities began restricting dual-use rare earth product exports to Japanese companies. This follows a pattern of escalating controls — gallium and germanium export licensing in 2023, antimony and graphite restrictions in 2024 — but the extension to rare earths carries particular sensitivity because it directly threatens Japan’s most competitive manufacturing sectors: EV motors, precision electronics, medical devices, and defense equipment. Against this backdrop of incrementally escalating restrictions, Sojitz’s decision to broaden its Lynas import portfolio represents both a preemptive defensive measure and advance preparation for what Japanese strategists increasingly view as inevitable further restrictions ahead.

Sign in to read the full article

Sign in with your AI Passport account to access this content.

Sign InDon't have an account? Sign up free